There has been a lot of research showing that fee-for-service (FFS) leads to increased medical service delivery and capitation leads to decreased medical service delivery. My own research shows that there are system-wide effects and that The impact of capitation for primary care physicians on services may depend on whether specialists are also reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis.. However, it is unclear how increasing the capitated reimbursement ratio affects the delivery of healthcare services. This is important for several reasons. First, CMS is increasingly moving toward alternative payment models that look more and more like capitation. Second, a large proportion of health care delivery in the United States is under mixed reimbursement schemes. Third, refund type varies by country; For example, in Norway and Denmark, FFS accounts for 70% to 80% of the total reimbursement, but in the family health organization plan in Ontario, Canada, the FFS portion covers only 10% of the reimbursement.

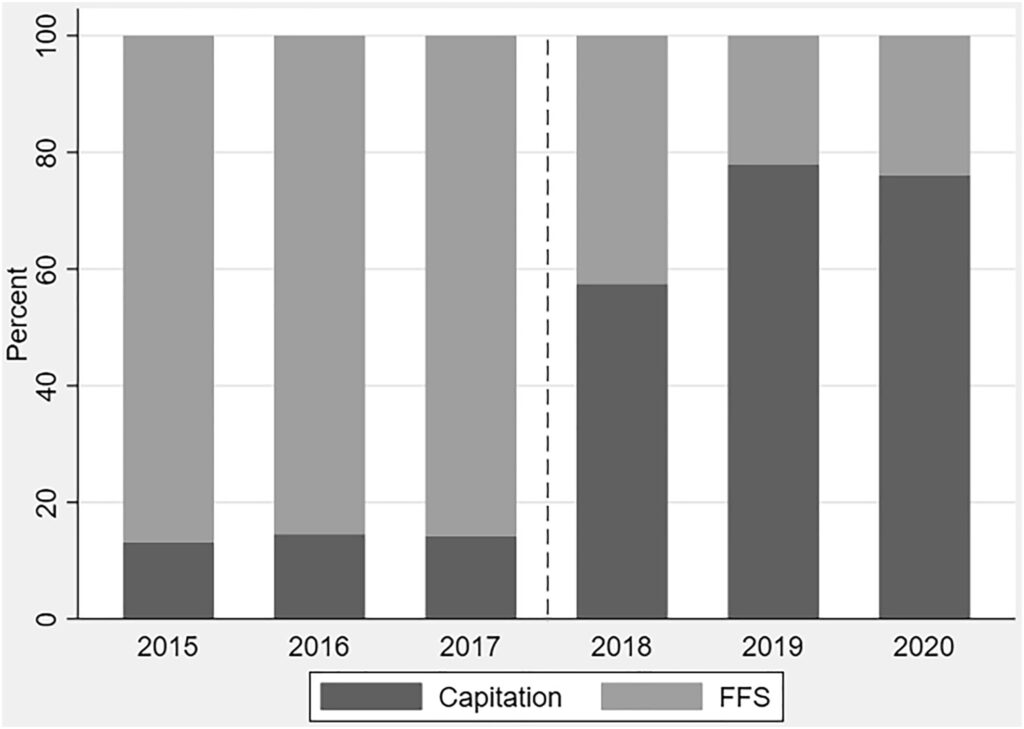

To examine this question, an article by Skovsgaard et al. (2023) uses a change to the reimbursement of general practitioners in Denmark in 2018, specifically for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes. The specific changes were as follows:

The new global capitation for patients with type 2 diabetes was set at 2045 Danish crowns (approximately US$280) per patient per year, in addition to the basic global capitation per patient. This amount was greater than the corresponding average FFS that was discontinued for patients with type 2 diabetes. Note that capitation replaced FFS for all contacts of patients with type 2 diabetes, not just diabetes-related contacts. The remaining FFS fees outside of the reform comprise a range of ancillary services including guideline-recommended HbA1c monitoring, influenza vaccination, and microalbuminuria testing through urine protein assessment. These guideline-recommended services are process quality measures that indicate whether changes in service delivery affect the quality of care.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/hec.4736

In terms of empirical strategy, the authors apply a difference-in-difference approach. The pre-post are the differences between results and interest before and after an annual control visit. The change in services for annual check-up visits in 2018-2019 compared to 2015-2016 is examined. Outcomes or interests were: (i) number of visits (in person, by phone, and email), (ii) number of diabetes-related laboratory tests (e.g., urine strips and HbA1c tests), (iii) flu vaccines, (iv) diabetes-related supplemental services, and (v) non-diabetes-related supplemental services.

Using this approach, the authors find that:

The effect of enrolling a patient in the new plan is negative with a reduction of about 2% compared to baseline (ATT = −0.27%; −1.9%)… the effect of enrollment on the complementary services (yes) related to diabetes guidelines is negative with a magnitude of reduction of about 4% compared to baseline (ATT = −12.29%; −4.4%)… The results [also] indicate reductions of 5.0%, 5.4%, and 4.2% compared to baseline for urine samples, blood samples, and influence vaccination, respectively.

To check the robustness of their findings, the authors examined services not included in the new reimbursement plan (for example, lipid-lowering medications) and found no effect in this placebo test.

The authors hypothesize that the reason the reductions in supplemental services were greater in magnitude than the reduction in visits was due to a replacement of face-to-face visits with telephone and email contacts that now allow immediate provision of supplementary services.

You can read the full article. here.